Early one afternoon last May, Walter Swift walked out of a pot-smoking session at a friend's house in Detroit and stepped straight into trouble: Two men forced him at gunpoint into an SUV.

Swift owed one of the guys $100 for drugs, and the time to pay up had come. The man now wanted at least $400.

The captors took Swift's cell phone and scrolled through it, looking for people to call in an attempt to get some quick cash. They blindfolded Swift and drove him around the city while they waited for someone to comply. Swift hoped those being called would contact the police, an odd feeling for a man who had recently spent 26 years behind bars.

Over the next several hours, the two men took furniture from Swift's Southfield apartment. They also took his keys, identification, driver's license, social security card, checks and reading glasses, and considered taking the washer-dryer unit that came with the apartment. And they continuously threatened him.

"They would just keep reiterating that I needed to get this money, things like, 'We should murk him,'" Swift testified, using street slang for "kill," at the men's preliminary examination on kidnapping and other charges that was held in July. "We should take him to the lake."

Fearing for his life, Swift tried to negotiate with his abductors, a skill he had developed in prison, where understanding the criminal mentality was one of the keys to staying alive.

Swift's kidnappers told him to "shut the fuck up." "You should know better," he describes them saying. "You know, you have been in prison before."

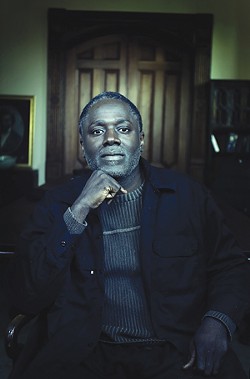

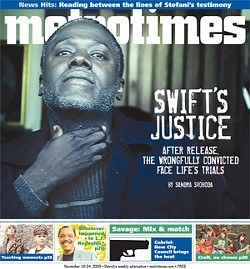

Convicted of raping a pregnant teacher in her Detroit home in 1982, Swift was released just 18 months ago, after attorneys found that lab tests excluding him as a suspect weren't included in his defense at trial. Police also used a questionable photo lineup to identify him. In May 2008, Wayne County Circuit Court Judge Vera Massey Jones reversed Swift's conviction. Wayne County Prosecutor Kym Worthy did not object. She agreed there were problems with his conviction but declined to declare him completely innocent.

Since then, Swift, like many exonerees, has struggled with his post-prison life. After years of incarceration, he's faced depression, anxiety and other challenges while trying to cope in a world he no longer recognizes. Eighteen months after regaining his freedom, he says every day is a struggle to survive.

"Why? Because in prison it's a necessity. You do it out of necessity, an instinct to survive, the will to survive. Here it's a choice. It's a choice to adopt the same culture, values, principles. It's a choice and it's very hard to shed a certain method of seeing things, a certain way of doing things willingly," says the 48-year-old Swift. "I've entered into another culture which is everyday society, and I have to re-learn it."

To say Swift has had problems is an understatement. He describes what researchers have said are the predictable, defining psychological effects of wrongful conviction: shock, betrayal, sense of injustice, a search for life's meaning and the loss of identity.

At times, Swift has addressed his troubles. He got some counseling and went to rehab for drug use. But he's also blown through tens of thousands of dollars raised for him since he left prison. His attorneys won't let him answer questions about exactly how much money or give details of his substance abuse.

But Swift is on the verge of filing a civil lawsuit against the city for what he says was the Detroit Police Department's role in his wrongful conviction and against Wayne County for the system that provided him a flawed defense lawyer.

And Swift will appear in court next month to testify against two men he says kidnapped him, but says his role as a victim and witness "conflicts" with his prison mentality. "You don't testify against people, particularly if you live a criminal lifestyle yourself," he says. "I'm an ex-con. I spent 26 years in prison ... engaging in questionable behavior."

Each day Swift was in, he says, was a struggle to not become a criminal like those surrounding him — nor one of their victims. Either role could have jeopardized the freedom he believed he'd someday have.

"My challenge was to somehow follow the prison norms and prison customs and traditions without letting it become a part of my psyche or my mentality," he says.

If Swift had been guilty, served his sentence and been released on parole, he would have had some help through the Department of Corrections. But as one of the small but growing number exonerees in Michigan whose convictions have been overturned, he was released from prison with no money, no place to live, no job, no medical or dental insurance, no mental or other health care. The exonerees emerge with the clothes on their backs, often provided by family just moments before their release. They're met on the sidewalk by emotional relatives, friends and attorneys, their tearful reunions recorded in newspapers and on the evening news. Then they head to a life of freedom but uncertainty.

About 1,500 Michigan men and women are released from prison on parole each year. With their sentences completed, they are eligible for job training, some medical assistance and other services through the Michigan Prisoner Re-entry Initiative. Between 13,000 and 14,000 parolees received some services in 2009, says spokesman John Cordell, with the Department of Corrections spending about $50 million, mainly on staffing for programs for them.

Exonerees, however, are ineligible. "For us as a state agency, we don't have any supervisory authority over them," Cordell says. "Those are the gaps that we don't have real good answers for or real good policies for."

Swift and others like him — there have been at least 10 people exonerated in Michigan since 2002 — get none of those benefits that they say would at least serve as a symbolic apology from the system that took years from their lives.

"Something there just isn't right," says Ken Wyniemko who served nearly nine years for a Clinton Township rape that DNA testing eventually proved he didn't do. He was released in 2003 and says he has "come a long way" in dealing with his wrongful incarceration and release.

"When I first realized I could get out, I thought I'd walk out the door and pick up the pieces dating back to 1994, but it doesn't work that way," Wyniemko says. His attorneys arranged for some counseling for him, which he at first resisted. "I thought I was strong enough to get by on my own. After all, I made it through nearly 10 years in prison. But you get to the point where it's almost embarrassing to admit to yourself and to those that are close to you that you need psychological help."

Wyniemko eventually won a civil suit against the township in his case. Such cases take years and aren't always successful. Individual prosecutors have immunity from actions they take at trial, but the U.S. Supreme Court is currently considering whether that applies in cases of prosecutorial misconduct. A second Supreme Court case involves standards for defense attorneys.

Exonerees and their advocates in most other states have successfully fought for legislation that provides financial, medical and other support for those who served time for crimes they didn't commit. But in the last two sessions, Michigan lawmakers have twice failed to enact legislation that would have done the same. New bills are currently languishing in legislative committees in Lansing with no hearings scheduled — and in an even tougher economic environment.

Meanwhile, the exonerees try to rebuild their lives without help from the state. In order for that reconstruction to be successful, they must address prison's lingering psychological issues, which are exacerbated by the injustice suffered, says C. Ronald Huff, professor of criminology, law and society at University of California-Irvine.

For decades Huff has studied the problem of wrongful convictions. He estimates at least 7,500 people are wrongly convicted each year in the United States for just the most serious of crimes: homicide, manslaughter, robbery, rape, assault, burglary, larceny, arson and car theft.

He's advocated for compensation and other assistance for exonerees who are released from prison.

"It's a horrible experience. There's a lot of trauma they suffer, and there's very little service provided," he says.

'Amazed at the support'

Across the country, more than 500 people have had their convictions overturned in the last decade, according to estimates from the Life After Exoneration Project based in Berkley, Calif. About half of those have been assisted by the national Innocence Project based at New York's Cardozo Law School, which uses the science of DNA identification to prove exonerees didn't commit the crimes for which they were convicted.

In Michigan, DNA has been used in the release of three men who were represented by lawyers from the national Innocence Project or its state affiliate at Cooley Law School in Lansing. Earlier this year the University of Michigan Law School launched its Innocence Clinic, which deals with wrongful conviction cases that don't have DNA evidence. Attorneys and students there have successfully argued for overturned convictions and subsequent releases of four people in the last few months, with hundreds of more potential cases in the pipeline.

People are wrongly convicted for a variety of reasons. Eyewitnesses get it wrong. Police and prosecutors are overzealous, focusing on one suspect instead of doing a more comprehensive investigation, or suppressing evidence of innocence in the worst cases. Jailhouse snitches lie. Suspects falsely confess to police under extreme interrogations. And defense attorneys are ineffective.

A Calhoun County woman says her case included many of those reasons. Lorinda Swain, 49, was convicted in 2002 of sexually molesting her adopted son. Before her trial, the then-teen told investigators he made the story up. Despite that recantation, police and prosecutors proceeded, corroborating the boy's story with Swain's supposed confession to another prisoner. She was found guilty and sentenced to 25 to 50 years in prison.

When her son turned 18 three years ago, he took up Swain's cause, telling anyone who would listen that he had lied. After two unsuccessful appeals filed by other attorneys, the Innocence Clinic convinced a Calhoun County judge to order a new trial for her. He agreed, but the newly elected prosecutor there is fighting the order. In August, Swain was freed but on an electronic tether pending a Michigan Supreme Court ruling on the trial order, which the appellate court upheld in September.

Swain, restricted by a tether to the county, is living at the farm owned by her parents, who spent tens of thousands of dollars on her legal battles. She takes care of the house and helps them and bakes pies for her hundreds of supporters. The community's faith in her innocence and efforts toward proving it have buoyed her. "I'm amazed at the support I have out there," she says.

At the time her son made the allegations against her, Swain was using drugs. She's now clean. "If I had to say one positive thing that did come from the eight-and-a-half years of incarceration, it was that my desire to use drugs is 100 percent gone," she says.

Swain hasn't been to any counseling since she's been out of prison. "If I went and I liked the person, I probably would go back. I don't think I need it. I'm a talker. I'm doing wonderful."

She says her family support and her ability to work some odd jobs has kept her grounded, but she knows it's early in her release and her case is still, technically, pending on the appeal. She calls it "bittersweet" right now.

She admits to having more hostile feelings about her case early in her prison term.

"When I was in prison I can remember feeling a lot of hate in my heart. I almost let it destroy me. I let it go."

And she's rebuilding her relationship with her son. "He's tried very hard to right his wrong, and I 100 percent forgive my kid," she says.

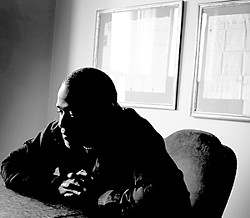

Wary of the world

Detroit resident Dwayne Provience is also recently free but living with an uncertain legal future. Provience, 36, had his conviction in the fatal shooting of Rene Hunter overturned earlier this month. In 2001, a Wayne County jury found him guilty on the testimony of a single witness, an admitted drug user who was in custody on suspicion of burglary when he told police that Provience had shot and killed another Detroit man. Although his description of the shooting contradicted seven other witnesses, Wayne County prosecutors used only his testimony at Provience's trial. The witness has since recanted his trial story, saying he wasn't at the scene.

Two years later, prosecutors would argue in a separate but possibly related shooting that it was another man — not Provience — who had killed Hunter. Judge Timothy Kenny released Provience on bond Nov. 3, while prosecutors pursue a new trial. Provience is living at his mother's house and has an electronic tether. He can't leave her property, but at least he's not locked behind bars surrounded by hardened criminals.

"It's OK. It's a good transition," he says of life with a cigarette pack-sized black device strapped to his right ankle. "I don't want to go back out there and get overwhelmed with everything."

The full reality of life after exoneration hasn't hit Provience yet, in part because his case isn't finished. A Nov. 24 hearing is scheduled at which he hopes prosecutors will give up.

But until then, he's been catching up with nieces and nephews born while he was in prison and renewing his relationship with his teenage son and daughter who come over every day after school to do homework and have dinner.

"I need to get back out of here and be the family man my family needs me to be, especially my children," he says. They've been on their best behavior, he says, without "real teenage issues" coming yet.

Prison helped him in some ways, he says. Having dropped out of high school, he earned a GED while behind bars and got certifications in custodial maintenance and biohazard cleanup. But he considers his incarceration far worse than that experienced by other inmates because he was innocent. He never got to the common stage of accepting responsibility for getting himself imprisoned.

"It makes it pretty difficult because you know you're in there for something that you didn't do compared to if you've done something and you're in there, you can accept the punishment a lot better than being innocent," he says. "It made it pretty difficult for the first few years but after that I had to not grow bitter or sour about the whole situation, I had to just stay focused and try my best to get a hearing to prove my innocence."

Provience's best friend while in prison, DeShawn Reed, was on the sidewalk to meet him when he was released from custody. Reed and his uncle, Marvin, had taken the same walk in July.

'Treated like animals'

On the testimony of Shannon Gholston, the Reeds were convicted of assault with intent to murder and sentenced to 20 years minimum. At their 2001 trial, Gholston said he'd seen Marvin Reed driving a car with DeShawn Reed shooting at him out the window as they drove through their Ecorse neighborhood in March 2000. Hit in the back of the neck, Gholston is a quadriplegic. DeShawn Reed and Gholston had gone to school together.

But about six years into Reed's sentence, he learned from a mutual friend that Gholston wanted to "tell the truth," that he never saw who shot him and instead testified based on what police and family had told him happened. In addition, after their trial, the gun used to shoot Gholston turned up on another Ecorse man, Tyrone Allen, when he was shot and killed by police during an attempted car jacking. Other witnesses at trial had named Allen as the shooter. The Reeds and their attorneys also say Ecorse police withheld evidence that could have helped clear them.

After a series of evidentiary hearings this spring, Wayne County Circuit Court Judge Patricia Fresard ordered a new trial for the Reeds, finding there was "a significant possibility that the defendants are innocent of the crimes in which they now stand convicted" she said.

Prosecutors dropped the case against them. The Reeds left prison July 31.

"We were so used to getting treated like animals through the years, and that just changed in a matter of minutes in how they started treating us when the media was outside," DeShawn Reed says. "They call you by your prison number and then they're calling us 'Mr. Reed' and extending their hand out to shake your hand."

After a few weeks of celebration with his four children and the rest of his family, Reed settled in to living at his mother's home and spending some time at the house where the mother of his oldest son lives. Relying on others bothers him.

"It kind of makes me feel like I'm still locked up, getting money from my family, them being responsible. It's odd," Reed says. "When you're living under somebody else's roof and it's not your own place, you've got to abide by their rules. And at the age I am, 34, it's like still limited to the things you can do in somebody else's house."

A few weeks after his release, Reed went to the mall. He had to leave in a panic. "It was just so many people I couldn't stay. When you're in the penitentiary, you're watching your back. When somebody's walking in back of you, you're thinking you're going to get hurt, stabbed," he says. "I lived a long time of just every day gotta watch your back, not knowing if you're going to be killed or something's going to happen to you. That was a whole bunch of years living like that."

Reed says he mostly restricts himself and stays at family members' homes and spends as much time as he can around his loved ones.

Three days after Reed was released, he was in his former Ecorse neighborhood with some friends when Gholston rode up in a van. "Shannon was just sitting there smiling. I opened the door. I gave him a hug and a kiss on the cheek. He asked me how I was doing," Reed says.

They briefly talked about the case and Gholston's testimony that helped free Reed, nearly nine years after Gholston's story had imprisoned him. "He was just telling me that it took a load off for him," to tell the truth, Reed says.

But closure has only come from Gholston among those who helped put the Reeds in prison. "Nobody else said nothing to me and Marvin yet to this day. They just took eight years of our life," he says. "We just walked out and nobody said nothing. Nobody tried to offer us no job to help us out, just nothing. If me and Marvin didn't have the family and the support system that we have ..."

He doesn't finish that thought.

Reed says the prison experience for people who are innocent — like him and his friend, Provience — is different than for the truly guilty. "A lot of people be sarcastic about that, but there are a lot of people in prison these days and everyone in prison is not innocent. And everybody in prison is not claiming to be innocent," he says. "If you're innocent, you can just tell [who else is] because they're just like you. They talk like you about their situation, just everything. Y'all click. You shy away from the guy who is in prison for something. You just keep your distance. When me and Dwayne met, we held on and we ain't let go."

Both men worked on their GEDs in prison; Provience obtained it, and Reed is still working toward his. Prison, he says, made him a better person because it was a wake-up call to "get off the streets." He realizes his lifestyle at the time he was arrested — a high school dropout, not having steady work and affiliating with people involved in questionable activity, including members of the Black Mafia Family drug ring — made him a likely suspect in the eyes of authorities.

"If you choose the streets over school and positive things, this is what will happen," he says.

Prison made him realize that. So he used his time there to read, work on his case and plan for his release.

But prison isn't like that for everyone, he says.

"If you're guilty and you're a murderer and you live your life like that on the outside, you'll get worse in prison. If that's not you, you're not capable of doing the thing you're in there for, you're innocent, prison will help you."

He worries now about finding a job. "Then, it'll be better," he says.

In the whirlwind

Swift describes a more complicated prison life — his time behind bars was more than three times as long as the Reeds', Provience's, Swain's or Wyniemko's — and he has lived a far different life outside since his release.

Eighteen months ago, he emerged from prison exonerated of the 1982 sexual assault. His Innocence Project attorneys found that evidence eliminating him as a suspect had been suppressed by Detroit police. Wayne County Prosecutor Kym Worthy joined the motion to have his verdict set aside, never admitting Swift was innocent.

Swift, like most other exonerees, was sprung with no apology, no compensation and no compassion from the system that convicted and imprisoned him. Once out, he had a circle of supporters who donated tens of thousands of dollars to help him. He immediately faced a crush of media attention and a life promising the freedom that was — at best mistakenly, at worst maliciously — taken away from him by the rape victim, police, prosecutors and a jury those decades ago.

The whirlwind whipped up quickly. Sponsored by a former law student who had worked on his case, he traveled to Ireland for a month of fund-raisers and celebrity-like appearances. At home, he enjoyed the support of boxing trainer Emanuel Steward. He had a suburban apartment strategically located across town and removed from the Detroit neighborhood of his youth, where he ran with gangs, stole cars and committed burglary.

He joined a gym. He worked at Fishbone's restaurant courtesy of its owner, Ted Gatzaros, and a construction company until he wrecked his car and had no transportation. He spent the money supporters had raised for him, eventually asking his attorneys for food and cigarettes.

But he struggled, especially feeling a sense of entitlement from a society that locked him away for a crime he didn't commit.

Swift is articulate, even charming, and manages somehow to seem both guarded and open at the same time. He has an edge the other men don't. His insight is immediate and complex. His intelligence is raw and unrefined. He has a suppressed energy that can draw sympathy from people around him but also a rough edge and an unpredictability that can be discomforting.

Swift admits the euphoria immediately following his release was replaced with anxiety, a classic symptom of the post-traumatic stress disorder that psychologists say can follow prison terms. Swift also reports bouts of depression and confusion, uncertainty about how to build a life outside of prison. "I didn't know what to do with it," he says of his discomfort. "I didn't know how to address it because at the same time I was experiencing other issues as well as far as trying to make a productive re-entry into society, and a lot of it was very, very overwhelming, and it resulted in some other issues coming up like drugs and things like that." He also found people in Detroit's "urban, inner-city community" to be "very accepting of criminal behavior."

And he admits the culture of prison for all those years changed him for the worse in some ways.

"A lot of the everyday practical aspects of living in society is very difficult for me. I'm better at it now, it being 18 months later, but in the initial stages of my release it was quite overwhelming," he says.

Rather than being the productive citizen he and his supporters had hoped, there was Swift, stoned and blindfolded, being driven around by one of his dealers and another acquaintance, fearful of being "murked" last May. They stuck a gun in his mouth and looked through his cell phone for people they thought would pay them.

One of the numbers they found in his cell phone was that of WXYZ-TV's Bill Proctor. They called him and Swift told him he was "in trouble" and asked for money. Proctor, a former cop, had interviewed Swift before his release and has since become one of his closest confidants.

When Proctor realized Swift was in danger, he called Detroit police who sent several cars out looking for him, eventually alerting Southfield police. After Swift's kidnappers dropped off his couch — just where, the blindfolded Swift can't say — they were returning to his apartment when they saw cops there. They headed then to Hamtramck where they released Swift, shaken but unharmed.

Two men were arrested and charged in the abduction. Their trial is set for Dec. 4.

Swift's main motivation in testifying against his alleged kidnappers is to see them convicted and imprisoned, ironically enough. He calls them "dangerous" and says they pose a threat to him and his family. One of the men charged fathered a child with Swift's niece.

But taking the stand against them serves another purpose, he says, one that is helping him find his own justice among the injustice he suffered.

After his brush with death, he sees this as a step in shedding the identity he adopted behind bars: "I have to — how should I say? — re-enter the values and concepts and the ideologies of mainstream society."

Sandra Svoboda is a Metro Times staff writer. Contact her at 313-202-8015 or [email protected]