DPS Transition Manager Judge Steven Rhodes announced days earlier that, come June 30, the district would run out of money and would be unable to pay teachers who opted to spread their salary out over 52 weeks.

"We thought the $50 million would let us to get through September," says James Porter, a teacher of 14 years, referring to the fact that less than two months earlier, the state legislature passed a $47.8 million "rescue package" for the sole purpose of avoiding such a scenario.

Walking around wearing a poster that read, "Would you work for free?" Porter joined hundreds of other teachers who wanted to know where the money went. Their rally goals were two-pronged: Demand pay for the work they'd completed, but also push for a forensic audit of the district.

"Given that the district was in a surplus when the state took it over in 1999, and now is in a substantial amount of debt, we want to see where the money has gone, and who needs to be held accountable for this situation we find ourselves in," says Joel Berger, an English teacher at Cass Technical High School, who points out that the Fisher Building, where the teachers were protesting, is a perfect example of mismanagement in the district.

In 2002, when DPS was under its first round of state control, the top five floors of the Fisher Building were purchased for $24.1 million to house the district's administrative offices. The not-so-funny joke? One year earlier, the Farbman brothers, who sold the offices to DPS, bought the entire building for $21.3 million.

"At the end of the day, students, parents, and teachers are suffering the consequences of failed emergency management of the district," Berger says.

While Rhodes told the teachers that they would be paid if they returned to the classroom (and if Lansing passed legislation addressing DPS), the demand for a forensic audit remains.

Getting it to happen, however, has become something of a challenge.

While the senate's DPS legislation passed weeks ago — before the demand for an audit was made known — the house did not pass their Putting Students First Bill until the wee morning hours on May 4. Not only could legislators have pushed for an audit, but the opportunity was presented to them.

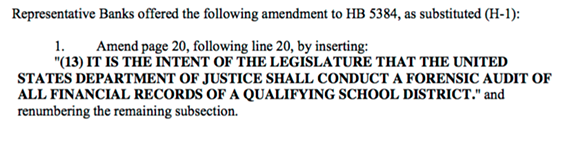

As the teachers chanted in front of the Fisher Building, Rep. Brian Banks (D-Detroit) made a motion in the Appropriations Committee for the district-wide audit.

"We've heard through talks and negotiations that the debt was one amount and then another and then another," says Banks, whose amendment specifically requested that an outside party, the Department of Justice, perform a forensic audit of the district.

"Seeing that DPS has received both federal and state dollars, and seeing that its had five emergency managers since 2009, it is my goal to bring in a separate entity to conduct an audit to see what has come in and what has gone out."

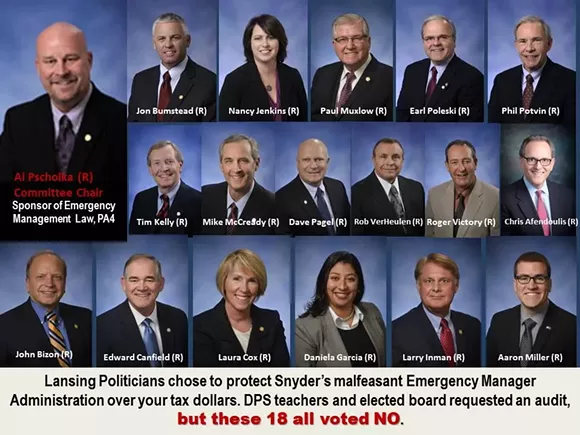

Banks' call for action, however, never made it past committee. Eighteen GOP representatives voted against it. Many of the very same legislators who have balked at the idea of spending state dollars on a financially insolvent district with so much "corruption" like Detroit.

"The House's rationale for being punitive to Detroit was asking, 'Where did the $30 million for MPSERS go?' Yet they really don't seem to want that question answered," says Thomas Pedroni, an associate professor of curriculum studies at Wayne State University, who has been studying the effects of the state's control of DPS. (It was announced last month that, from June 2014 to February 2016, DPS received $30 million from the U.S. Department of Education that was never properly forwarded to the Michigan Public School Employees Retirement System.)

"Fiscally conservative taxpayers who voted those representatives into office surely would be interested to know where the hundreds of millions of dollars they are being asked to foot the bill for went," he continued.

Why would anyone be against bringing more clarity to how funds have been spent over the years?

Facebook

A meme floating around the internet follows the house appropriations vote that shut down the audit amendment.

We decided to call and find out.

MT emailed and called (leaving voice messages) for all 18 legislators: Reps. Al Pscholka, Jon Bumstead, Nancy Jenkins, Paul Muxlow, Earl Poleski, Phil Potvin, Tim Kelly, Mike McCready, Dave Pagel, Rob VerHeulen, Roger Victory, Chris Afendoulis, John Bizon, Edward Canfield, Laura Cox, Daniela Garcia, Larry Inman and Aaron Miller.

We heard back from three: Miller, a former teacher who now represents District 59, which is 2 1/2 hours away from Detroit; McCready, a former businessman who works with commercial furniture manufacturers and represents District 40 (the Birmingham and West Bloomfield area); and Inman, who spent years working as a loan adjuster for Huntington National Bank and represents Grand Traverse County — four hours from Detroit. (Random factoid: Inman has one of the world's largest collections of Amelia Earhart-related artifacts.)

While we want to give props to these three representatives for returning our calls — it seems absurd that the other public servants would be unable to explain their voting records — their answers did not give total clarity for why the audit was denied, though some valid points (i.e. costs) were raised.

So let's start with Miller, who has previously been quoted as saying: "No kids in Colon, White Pigeon, Marcellus, or Dowagiac should pay for the repeated mistakes of administrators and boards in Detroit ... ever."

Miller's reasoning for voting down the amendment was that he didn't have enough time to sit down and go over the amendment — it came really fast.

He also points out that Financial Review Committee, which is part of the bigger house bill, and would be in charge of reviewing future DPS spending, could always go back and demand their own audit.

When we pointed out that the FRC deals with the future — and this amendment was calling for an audit of the past, since so much of DPS's current finances are obscured — Miller suggested that the forensic audit (which his vote helped squash) should go back even further than 1999. "In my mind, emergency managers softened what would have been a bigger financial blow," he says.

This comment shouldn't have surprised us, on Miller's Facebook page he recently wrote, "Detroit has an operating debt of about $515 million and, in committee, many minority party members and many Detroiters were trying to argue that the state created this debt with the emergency manager system. That's preposterous. Past audits show that those claims are blatantly false."

We pointed out that DPS's deficit has blossomed under emergency management — as the New York Times explained, "The district’s year-end budget deficit ballooned to a projected $320 million this year from $94 million in 2013."

"It could have been much worse," Miller says.

We pointed out that many of DPS's fiscal woes are due to competition with charter schools. Did Miller vote in favor the Detroit Education Commission, an appointed board that would monitor openings and closings in the city, we asked? No.

While we knew Miller was skeptical of charter schools from previous interviews, the explanation for his vote sounded eerily similar to those of the pro-charter lobby: that charter schools would not be treated fairly under the appointed board, and that it would become too political.

McCready and Inman, on the other hand support the DEC (it is not included in the house's current bill). The representatives, like Miller, however, did not believe the state was in a position to demand a forensic audit. Rather, they hoped this would be something the reformed future DPS would take up on its own.

"In DPS, there used to be an inspector general for fraud and abuse, and then the EM cut that position. It was my hope that if we re-established a local school board with the DEC, they would restore the inspector general's office, and they could handle this internally," McCready says, pointing out that Rhodes has recommended that the office be revived.

Again, this fails to bring in a third-party — any inspector general would still be working for DPS, as Banks explains — and it does not promise that an audit would include previous years, as a forensic audit does.

"Forensic audits are much more detailed," Inman explains, pointing out that because they require more investigation (i.e. following a check from start to receipt) they can take up to a year to complete and cost an average of $500,000, if not more for an institution the size of Detroit. "Usually forensic audits are recommended when we see problems with internal control, unbalanced books, and large discrepancies in check books."

When we pointed out that this sounds like the current situation in Detroit (Inman had, moment earlier, told us that Rhodes and the state Department of Treasury were currently unable to give the legislators current figures for the district) he questioned where the money for the audit would come from and how long it would take, later adding: "I am not opposed to a forensic audit being done on DPS. I just don't think it should be required."

In Inman's opinion, this should be a decision that the FRC, which Miller also mentioned, should make.

"It's my opinion that the Financial Review Committee would be responsible for reviewing concerns about financial management of DPS. They would have the authority to call for a forensic audit. It would be at their discretion, and not the legislature saying they have to."

This answer doesn't suit all, especially teachers who remain puzzled as to why they've been scapegoated throughout much of the debate over the district's future. After years of mismanagement under state-appointed emergency managers, will the state-appointed FRC really call for a forensic audit? Is this something a financially insolvent district should be on the hook for? These are questions teachers are asking.

"Many House Republicans seem to blame us, those who have been rendered almost completely powerless and voiceless under state control of the district," says Cass Tech's Berger. "It is wrong, and we hope that an audit will shed light on who is truly responsible for this situation."

"Michigan legislators have refused to audit the finances of DPS. We set up a lemonade stand to help them fundraise. Now what's the excuse?" says DPS teacher Nina Chacker, right, who stands with fellow DPS teachers Zack Sweet and Kiarra Ambrose.

While the audit is currently off the table in senate and house legislation, that hasn't stopped teachers from pushing for one. Three DPS educators held a lemonade stand outside of Eastern Market last Saturday to "raise" the $500,000 they would need. While the goal was clearly a long shot, DPS teacher Nina Chacker, one of the organizers, says the stand was less a fundraiser and more a call to action.

"The lemonade stand was a push for accountability," says Chacker. "We wanted to bring this to people's attention and let them know we don't have to accept this reality where people tell us there is a problem and then we have to trust them to come with the best solution. We've trusted them in the past and they've run us into the ground."

Without a forensic audit, says Chacker, DPS will likely end up in the same, financially tenuous position.

"Everyone wants to know how taxpayer money is being spent, even people who want a totally different outcome for DPS want to know where money has gone," she says. "It's a unifying issue for everyone involved."